The Show Trial of Paul Shanley

[From the May 2005 issue of The Guide. Editor French Wall. Fidelity Publishing, POB 990593, Boston MA 02199-0593. email: theguide@guidemag.com. 617/266-8557 fax:617/266-1125]

[Copyright 2005 by Jim D’Entremont. Anyone may link to this page without explicit permission. Requests to repost all or part of this article on electronic systems serving fighters for justice are encouraged. All repostings must retain this copyright notice in its entirety. Send permission requests to jim@freebaran.org.]

The ordeal of Paul Shanley, a 74-year-old ex-priest accused of rape by a former Sunday School pupil, should have been a turning point in the sex-abuse panic that churns through American culture. His prosecutors’ version of events hinged on one accuser’s uncorroborated “recovered” memories of long-term abuse. The trial, telecast by Court TV, could have certified the unreliability of such evidence, forestalled its future deployment in Massachusetts courts, and discouraged its use in other jurisdictions.

But on Monday, February 7, after nearly two full days of deliberation, a jury of seven men and five women found Shanley guilty on two counts of child rape and two counts of indecent assault and battery on a child under the age of 14. During the two-week trial process culminating in that verdict, fresh disinformation about repression of traumatic memory was pumped into public consciousness almost daily. Judge Stephen A. Neel ordered Shanley imprisoned from 12 to 15 years, a probable life term.

The case against Shanley was a volatile mixture of folklore, bigotry, fever heat, opportunism, and tainted whimsy. The trial, held at Middlesex Superior Court in Cambridge, Massachusetts, almost didn’t happen. Since the alleged offenses were said to have occurred between 1983 and 1989, the timing of Busa’s accusation scraped the margins of criminal and civil statutes of limitation. In the months between Shanley’s May 2002 arrest in San Diego and the conclusion of pretrial hearings, his accusers dwindled from four to one.

By that time, several factors had made the former “hippie priest” a national emblem of clerical sex-abuse. On January 31, 2002, the Boston Globe had launched a smear campaign against Shanley as sidebar to a superheated, Pulitzer-grabbing series about priestly depredation and Archdiocesan cover-up. Few observers noted that a decades-old vendetta between the Globe and the Archdiocese of Boston — WASP and Catholic power brokers sparring for political leverage, especially within the Massachusetts Democratic Party — was submerged in the growing, media-driven scandal. Hardly anyone objected to the Globe‘s reliance on innuendo. The one up-front Shanley accuser the Globe was able to produce was Arthur Austin, then 53, a man who had sought guidance from Shanley at age 20 after breaking up with his boyfriend. Austin had then become involved with the priest for six years.

“Closure” & Blood Lust

Scene from an Auto-da-Fé

Paul Shanley’s sentencing took place on February 15. Shanley now refers to the session as “my hanging.”

It was like a picnic at a lynching, one of those celebratory occasions when white folk posed for photographs below suspended corpses of black men suspected of miscegenation. Television news teams turned out in force. The spectators were in a jovial mood as they filed through a metal detector. Inside the courtroom, there were lots of big, warm hugs.

Introducing herself to strangers, a woman kept announcing, “I’m Dale Walsh and I’m a Shanley survivor.” Arthur Austin, dressed plumply in black, a small gold cross adorning his chest, a book tucked under one arm, stood greeting his fans. Attorney Mitchell Garabedian, a pioneering instigator of priest-abuse lawsuits, made an appearance. Also present were members of Paul Busa’s family, the Fords, former St. Jean’s parishioners, members of SNAP (Survivors Network of Those Abused by Priests), and Robert Curley, the activist father of a Cambridge, Mass. ten-year-old killed in 1997 by a man purportedly crazed with lust by the NAMBLA website.

“You’re catering to the NAMBLA contingent,” sneered Curley when a bailiff moved a group of Shanley supporters away from the Busa entourage and into the jury box, telling them they could “see better over there.”

When a delay was announced, someone cracked, “Shanley called in sick,” producing an outbreak of titters. Eventually, at 10:15 a.m., the session began with victims’ impact statements.

“This verdict is a tremendous relief and a source of satisfaction,” said Paul Busa’s father, a member of the Mass. Department of Correction’s fugitive squad. “What [Shanley] did to my son can never be fixed… he robbed my little boy of his innocence…. I’ve seen a lot of evil people, and I want you to know he’s right at the top of the list.”

Weeping, Theresa Busa recalled missing family weddings and baptisms because her husband found events where priests officiated far too painful to attend. She described Busa’s anguish and fits of temper, blaming the spectrum of his emotional problems on Shanley. Citing the pastor’s “indescribable crimes,” she said she hoped her husband’s tormentor would die in prison, ask God for forgiveness and be denied, and spend eternity in Hell.

Paul Busa’s statement, toned down from one submitted earlier, was read by prosecutor Lynn Rooney. Busa described Shanley as “the lowest of the low… a pedophile, possibly the worst ever.” As if stating fact, Busa went on to say, “He is a founding member of NAMBLA and he openly advocates sex between men and little boys.” He complained that Mondano’s cross-examination had “put my family and I through a living hell.” He expressed a wish that Shanley would “die in prison of natural causes €“ or otherwise.”

The statements contained no vestige of the Roman Catholic traditions of forgiveness, charity, grace, and redemption.

As the judge began reading the sentences €“ 12 to 15 years on two charges, 10 years’ probation on two more €“ a pair of bailiffs swooped down on Shanley and put him in shackles. Caught by surprise, Shanley flinched. Spectators uttered a satisfied moan.

As the hearing ended, someone whooped; others applauded. Arthur Austin made a beeline for the television cameras. Most people lingered near Paul Busa, hero and star.

Dissenting from the vow of celibacy imposed on priests since 1139, Father Shanley had consensual sex with a number of adults and teenagers over more than two decades. He also disagreed with the doctrine that all non-procreative sex is sinful. He frequently clashed with the Archdiocese of Boston on matters ranging from his support of Dignity, the unofficial organization of gay Catholics, to his refusal to sign a loyalty oath. Archdiocesan officials tried in vain to muzzle Shanley, whose positions on sexual morality were publicly aired on occasions such as the first National Conference on Gay Ministry in 1974.

When Cardinal Humberto Medeiros, Archbishop of Boston, called Father Shanley “a troubled priest,” he alluded to Shanley’s deepening involvement in the gay community — not to real or imagined instances of sex with children. Contrary to legend, Shanley was neither a founder of the North American Man/Boy Love Association (NAMBLA), nor an attendee at its first meeting, nor a member of that tiny, immensely despised organization. Nor did he promote sex between men and boys. Throughout Shanley’s career, most complaints regarding his behavior came from individuals offended by his vocal defense of gay rights.

From the late 1960s through the 1970s, an era of shifting social mores and widespread promiscuity, Father Shanley gave counseling to hundreds of teens and young adults who had parted company with mainstream America. It was a time of rebellion against the lingering repressions of McCarthyite anticommunist fervor, the brutalities of Vietnam, and the flag-swathed, sugar-coated pieties of Middle-American life. Following 1967’s “Summer of Love,” Boston became a hippie Mecca, the East Coast answer to San Francisco. Drawn to Boston and neighboring Cambridge by a large, antiwar student community and its drug scene, countless teenaged runaways encamped on Boston Common, in Back Bay crash pads, and around Harvard Square.

By the ’70s, Shanley had become a public figure, lauded for his nearly single-handed work with street people. Social workers considered his officially sanctioned Ministry to Alienated Youth an essential resource. Increasingly, as young vagrants turned to obvious methods of survival, the ministry became focused on male and female prostitutes in their teens and twenties. Shanley’s non-judgmental, non-authoritarian approach inspired trust. He was credited with saving lives.

In the winter of 1977-’78, a scandal erupted involving teenaged male hustlers and their johns who had been trysting at an apartment in Revere, a working-class town north of Boston. Echoing Anita Bryant’s “Save Our Children” campaign, then at its height, Suffolk County District Attorney Garrett Byrne launched an anti-gay witch hunt. With the aid of local media, Byrne’s campaign destroyed careers, devastated families, and precipitated suicides.

During the “Revere Sex Ring” hysteria, Father Shanley was one of several clergymen, doctors, and lawyers invited by Boston gay activists to speak at a forum on the issues raised by the crisis. His remarks included an account of a case where a young teenager was traumatized by the arrest and prosecution of a man who had been his benefactor. Shanley said he found the heavy-handedly punitive suppression of the relationship “worse than whatever you want to call the original operation, whether it was sick, or cynical, or criminal — the cure does far more damage.” He also observed that it can be “the man who is being exploited by the boy,” and that he believed that factors rendering sex destructive included force, money, incest, and lack of attraction.

Shanley did not attend any of the caucuses that followed the panel discussion. One resulted in the formation of GLAD (Gay and Lesbian Advocates and Defenders); another led to the founding of NAMBLA.

In 1979, Cardinal Medeiros terminated Shanley’s Ministry to Alienated Youth and reassigned the priest to St. John the Evangelist parish in Newton, Mass. The church — St. Jean l’Évangéliste to the French-Canadian Catholics it originally served — was known as “St. Jean’s.” Shanley’s duties included overseeing lay teachers who conducted Confraternity of Christian Doctrine (CCD) classes every Sunday. He remained at St. Jean’s as pastor to its predominantly white, middle-class congregation until 1990, when he went on sick leave and moved to California.

Newton, an affluent community with a component of blue-collar Catholics, has a reputation for left-leaning politics. Nevertheless, the Boston suburb is the epicenter of anti-gay political activity in Massachusetts. Newton is the home of the evangelical Massachusetts Family Institute; the birthplace of the militantly homophobic, anti-sex-ed Parents Rights Coalition; and headquarters for the crusade to ban gay marriage in the only state that now permits it. In this city of 84,000, moral panic is always ready to erupt around gay issues.

In February, 2002, it erupted at the home of 24-year-old Gregory Ford, who had attended CCD classes at St. Jean’s as a child. A veteran of 17 halfway houses and mental institutions, Ford had often accused people — though never Paul Shanley — of sexual abuse. Soon after his parents brought the January 31 Boston Globe article to his attention, however, Ford said that long-repressed memories of being dragged off by Shanley to be raped in bathrooms and confessionals came to the surface. The abuse supposedly began when he was six and continued for years. It was the first time anyone had claimed that Shanley was sexually interested in prepubescent children.

Ford hired a personal injury lawyer. The impulse toward litigation was encouraged by the recent success of other purported abuse victims in obtaining financial settlements from the Archdiocese of Boston without the inconvenience of investigations, let alone court proceedings.

Greg Ford’s recovered-memory claims, reported with minimal skepticism, inspired others. His former classmate Paul Busa said memories of rapes across a six-year period “came flooding back” after his girlfriend — now his wife — called him on February 11, 2002, at the Colorado Air Force base where he was stationed as a military police officer. She informed him that Ford was pursuing a lawsuit, claiming abuse by Father Shanley. Busa telephoned Ford and then Roderick “Eric” MacLeish, Ford’s lawyer, before reporting to an Air Force psychologist and requesting permission to return home to discuss a class-action suit.

On April 8, 2002, in the ballroom of the Sheraton Boston Hotel, MacLeish conducted a PowerPoint blitzkreig against Shanley. He produced 800 pages of Church documents, none of which actually implicated Shanley in sex with little boys. Since hardly anyone bothered to read the documents, reporters misrepresented their contents with impunity. MacLeish’s presentation was followed by lachrymose appearances by Greg Ford’s father and by Arthur Austin, characterized by David France in Our Fathers: The Secret Life of the Catholic Church as “the poet laureate of the Shanley attackers.” (Others have called Austin “the ex-boyfriend from hell.”)

MacLeish’s dog-and-pony show was effective. Victims’ advocates screamed for blood. A sex-abuse media frenzy coalesced around Shanley, whose arrest became inevitable. A reporter for WBZ-TV, Boston’s CBS affiliate, tracked down Shanley’s California residence and trumpeted his find on the air as if he had nailed a desperate fugitive. On May 2, 2002, Middlesex County District Attorney Martha Coakley then felt compelled to have Shanley taken into custody without the usual investigative process. The priest was spirited away and held on $750,000 bail.

MacLeish’s firm was soon handling more than 250 lawsuits citing abuse by Catholic clergy. In the June 2003 issue of Forbes, Daniel Lyons noted that lawyers had created “a billion-dollar money machine, fueled by lethal legal tactics, shrewd use of the media, and public outrage so fierce that almost any claim, no matter how bizarre or dated, offers a shot at a windfall.”

The beleaguered Archdiocese of Boston, having announced a “zero-tolerance” policy toward priestly impropriety, began dispensing money like an ecclesiastical ATM, doling out $85 million to 550 alleged victims by the end of 2003. In April, 2004, the Shanley accusers, whose ranks had expanded to four, received settlements now known to have been above the announced $300,000 Archdiocesan cap on individual reparations packages. Paul Busa alone received over $520,000. Soon after the payoff, Archbishop Sean O’Malley announced that Shanley had been defrocked.

During the lengthy period preceding Shanley’s trial, attorney Frank Mondano was able to win a reduction in bail that gave his client a respite of low-profile freedom. Meanwhile, Ford and Busa’s ex-classmate Anthony Driscoll was claiming to have recovered memories of Shanley assaults as well. (The trigger was lunch with Ford and MacLeish.) In the summer of 2004, however, Driscoll, a compulsive gambler, was dropped from the criminal case against Shanley, together with Greg Ford, whose narrative inconsistencies were getting acute. The fourth, more shadowy St. Jean’s alumnus, a heroin user without a permanent address, was nowhere to be found by the end of pretrial hearings.

Heading Shanley’s defense team, Mondano had greater success at preliminary court proceedings than at the actual trial. Dan Brown, the prosecution’s expert witness, was exposed as a crackpot. Sunday school teachers from St. Jean’s swore that, contrary to accusers’ stories, Shanley never came into class and departed with children in tow. As the case deteriorated, D.A. Coakley offered Shanley a two-and-a-half year probationary arrangement in exchange for a guilty plea. Maintaining his innocence, Shanley refused.

On the eve of the trial, the remaining accuser, Paul Busa, now a 27-year-old Newton firefighter, was reluctant to cooperate. Although he had once seemed to savor being cited by the press, he suddenly refused to testify if named in print or on the air. An injunction Coakley obtained forbidding publication of his name was voided on First Amendment grounds, but media refrained from naming Busa anyway. A ban on publishing or broadcasting images of Busa, his wife, or his father remained in place.

The trial began on January 25. The usually camera-hungry Martha Coakley receded into the background, perhaps fearing embarrassment. The prosecution was entrusted to Assistant D.A. Lynn Rooney, who had obtained the conviction of John Geoghan, a defrocked priest strangled in prison in 2003.

Shanley weathered his predicament with imperturbable dignity, though his demeanor seemed sinister to those who had prejudged him as a predatory pervert. The jury and the public never encountered Shanley as a human being. He did not testify. No character witness was called, though family members — notably his niece, Teresa Shanley — and a number of past associates remained implacably loyal. As the trial wore on, Mondano seemed distanced from Shanley, behaving as if his client were not even present.

The prosecution called a parade of witnesses, some of whom seemed to assist the defense. Former CCD teachers asserted again that Shanley never pulled children out of class; they did not remember sending pupils to Shanley for discipline. Former classmates testified that unruly CCD pupils told to leave the classroom would normally stand outside until invited back in. Brendan Moriarty, 27, described reporting once to Shanley, who sent him directly back to class with an admonition to behave. It was noted that St. Jean’s was a busy, public place, and that the pastor, who had to say Mass right after the 50-minute CCD classes, would have had few opportunities to carry on programs of sexual assault.

Mondano may have erred in representing Paul Busa as a liar rather than a man convinced his version of reality is true. When Busa testified, courtroom spectators witnessed scenes unavailable to TV viewers who could not see his face. Shanley’s barrel-chested adversary was aggressively histrionic — making faces, rocking, whimpering, shifting from side to side. At one chilling moment, he stared into space and snarled. He faced Mondano with sarcastic fury. One skeptical observer called Busa “a typical victim/survivor drama queen.” Others saw his performance as a heartfelt expression of pain by a man who had been groped, fellated, and digitally penetrated by Paul Shanley.

There are, however, many conduits of pain in Busa’s background. His parents separated when he was small; his early home life was often violent. He has a history of alcohol and gambling problems. Dreaming of a career in Major League baseball, Busa began using steroids at 16 and went on using steroids in the Air Force. Many of the physical symptoms he and his wife attribute to a powerful resurgence of traumatic memory are consistent with drug withdrawal.

The product of a lower-middle-class Catholic culture steeped in homophobia, Busa denied despising gay men. But in his journal — an exercise recommended by a military therapist in February 2002 — he repeatedly called Shanley a “faggot” or a “fucking faggot.” Detective reports quote Teresa Mazzei Busa as saying that Paul was “disgusted by homosexuality, and would get very upset about commercials that showed children naked.”

The D.A.’s Office replaced its original expert with Dr. James Chu, a psychiatrist based at McLean Hospital in Belmont, Mass., and at Harvard Medical School. Mondano’s cross-examination elicited admissions from Chu that there is an “intense level of polarized controversy about recovered memory,” that false memory does occur, and that self-reporting without corroboration poses problems. But Mondano neither challenged Chu’s claims about the reality of massive repression of traumatic memory nor took issue with his observation that such repression is likelier where there is a pattern of repeated trauma.

Research might have armed Mondano with the knowledge that Chu belongs to the Leadership Council on Child Abuse and Interpersonal Violence, a politicized organization noted for zealotry. The defense never addressed Chu’s belief in such dubious concepts as “body memory,” or documented his role in the Satanic Ritual Abuse scare of the 1980s. Nor did it probe Chu’s involvement with the International Society for the Study of Dissociation — formerly the International Society for the Study of Multiple Personality Disorder, founded by Dr. Bennett Braun, whose license to practice medicine was suspended in 1999 when patients’ lawsuits exposed his methods as quackery.

The sole defense witness was Dr. Elizabeth Loftus, a scientist based at the University of California at Irvine. Past president of the American Psychological Association, Loftus is the only woman the Review of General Psychology lists among the top 100 psychologists of the 20th century. She has done groundbreaking work on the reliability of memory, demonstrating again and again that false memories can be implanted by a range of sources.

The defense could not have picked a more distinguished expert, but Mondano seemed not to know quite what to do with her. He did at least focus on ideas. Lynn Rooney took the low road, ridiculing Loftus’s experiments, portraying her as a professional expert witness, and suggesting that, in contrast to Chu, a clinician, Loftus lacked knowledge of real, suffering patients. She characterized Loftus as a friend to child molesters. Mondano made no effort to repair the damage.

The jury was not told that repressed-memory evidence is inadmissible in a growing number of jurisdictions, including the neighboring state of New Hampshire, and has been discredited in nearby Rhode Island. Jurors never heard that Busa was the last of four dubious accusers who had all “recovered” memories of abuse, or that these were the only instances where Shanley had been accused of sexual interest in prepubescent boys.

In her closing argument, Rooney conflated dissociative amnesia with ordinary forgetting. She disregarded Judge Neel’s warning not to “elicit sympathy,” using monitors to flash images of little Paul at the time when Shanley was said to have been mauling him, years before he transformed himself into the steroidal hulk he is today. “[Shanley] would touch Paul Busa’s penis!” she exclaimed. “He would put his mouth on Paul Busa’s penis!” Urging jurors not to get distracted by the facts, she told them, “Use your common sense.”

In convicting Shanley, the jurors — all of whom had prior knowledge of publicity surrounding the case — ignored the judge’s clearly enunciated charge to determine guilt or innocence based on the evidence and beyond a reasonable doubt. Faced with an absence of evidence, they seem to have based their verdict on pop therapeutics and biased guesswork. One key factor, juror Victoria Blier told reporters, was that Busa had “won” a financial settlement from the Church (albeit out of court and sans evidentiary process). Other jurors found it relevant that the defense provided just one witness, Loftus, who seemed too “lofty.” The repressed-memory aspect of the case, they thought, made sense.

Attorney Chris Barden, who has triumphed in major lawsuits on behalf of ex-patients of recovered-memory and MPD therapists, calls the Shanley case “an anomaly,” insisting that the recovered-memory controversy played itself out in the 1990s. But recent accusations against priests suggest a resurgence of belief in the phenomenon in popular culture and among law enforcement officials.

Church positions on divorce, abortion, contraception, and homosexuality have created unaddressed resentment and distress among Catholics worldwide. Accusations of child molestation by priests provide a socially acceptable means of attacking the Church, and a common outrage among straight conservatives trapped in bitter marriages, overburdened families, and anguished members of sexual minorities. All seem to crave a respectable way to work out feelings of spiritual betrayal.

Between 1950 and 2003 there were 10,667 accusations against Roman Catholic priests and deacons across the United States. The accusations ranged from ambiguous fondling to unequivocal rape; criteria for substantiating incidents varied locally. Nearly a third of these cases were never investigated, because the accused had died or left the priesthood, or because self-described victims came forward well past statute-of-limitation deadlines. A report published by the John Jay College of Criminal Justice notes that 42.5 percent of the accusations date from 2002-’03, a period of media-spiked panic. US Department of Education figures suggest that students are far likelier to be abused by teachers and staff at secular schools than by priests.

Gay priests engulfed in this maelstrom are shunned by the gay community and accorded no help or understanding by the Church they serve. The late Pope John Paul II blamed the scandal on American permissiveness and the existence of homosexual priests. The organization Opus Bono Sacerdotii, one of the few resources available to accused priests from within the Church, promotes the Catholic ex-gay organization Courage, and endorses Pope John Paul II’s characterization of homosexuality as “intrinsically disordered.”

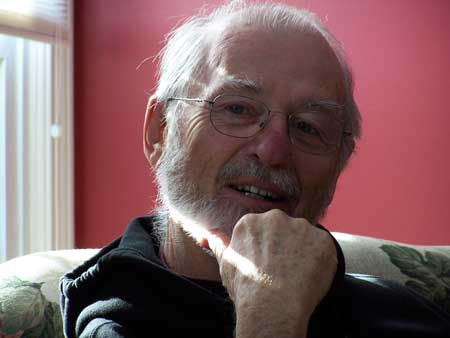

Paul Shanley is presently confined inside the walls of the Massachusetts Correctional Institution at Concord, pending possible transfer to another prison. For now, he does not fear for his personal safety. He spends his days reading, exercising, following an inmate’s routine.

“I think about what I’m doing at the gym, and what’s for supper,” Shanley says. “I don’t think much about my life, because the anger could destroy me.”