The Pending Trial of Paul Shanley

[From the December 2004 issue of The Guide. Editor French Wall. Fidelity Publishing, POB 990593, Boston MA 02199-0593. email: theguide@guidemag.com. 617/266-8557 fax:617/266-1125] [Copyright 2004 by Jim D’Entremont. Anyone may link to this page without explicit permission. Requests to repost all or part of this article on electronic systems serving fighters for justice are encouraged. All repostings must retain this copyright notice in its entirety. Send permission requests to jim@freebaran.org.]

Prosecutors, victims’ advocates, and media had for three years been spinning legends of Paul R. Shanley’s sexual insatiability, portraying him, in the words of one victims’ rights proponent, as “the worst of the worst” in the latest wave of priestly abuse scandals. But as its January 18 trial date approached, the Massachusetts child-rape case against the former Roman Catholic priest appeared to be unraveling strand by strand, with four accusers dwindling to one.

Martha Coakley, the politically upward-looking DA of Middlesex County, an area between the northern rim of Boston and the southern border of New Hampshire, still refused to acknowledge that the case was never more than a flimsy tangle of spectral evidence and wishful thinking. (See The Guide, June 2002.) As the prosecution totters forward, its credibility depends fully on the much-discredited notion of “dissociative amnesia” — repression of traumatic memories awaiting retrieval in therapy or through some triggering event.

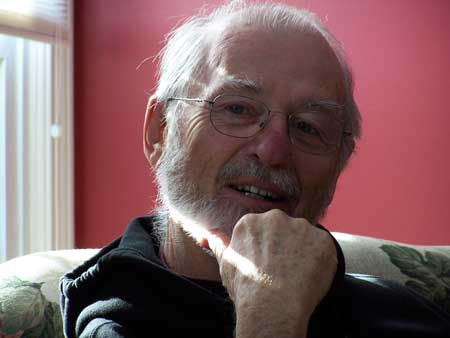

Shanley, now 73, was taken into custody at his home in San Diego, California, on May 2, 2002, and spirited off to Massachusetts to face charges. His arrest followed lurid, highly publicized accusations by two young men, Gregory Ford and Paul Busa, now 27. The former classmates claimed Shanley had plucked them out of catechism class for regular sessions of “oral and anal rape” during the 1980s. The abuse was said to have begun when the boys were six years old, and to have taken place in Newton, Massachusetts, during Shanley’s tenure as pastor at St. John the Evangelist Parish.

Greg Ford, an alumnus of 17 mental hospitals and halfway houses, has a history of drug use, violent behavior, lying, and accusing people — including his father — of having raped him. Nevertheless, Ford’s claims that a Boston Globe article on the ex-priest brought submerged memories of abuse by Shanley into consciousness elicited instant widespread credibility.

Paul Busa, a military police officer stationed in Colorado, began weaving his own allegations shortly after his girlfriend brought a newspaper account of Ford’s tale of abuse to his attention. Busa also began claiming to be shaken by emerging memories of abuse — but not so shaken that he forgot to make immediate queries about launching a lawsuit. He was the first to press charges against Shanley, who was arraigned four days after his arrest on three counts of sexual assault on a child. Additional charges were piled on when Ford, initially focused on suing the Archdiocese of Boston, came into the criminal case along with two other men who claimed to have retrieved memories of traumatic sex with Father Shanley.

The charges against Shanley have a strong subtext of homophobia. The January 31, 2002 Boston Globe article that spawned the case — a McCarthyite exercise in innuendo — seemed predicated on the idea that a gay priest who ran a youth ministry would of course prey on his flock. The one above-ground accuser the Globe was able to produce, however, had entered into a consensual relationship with Shanley at age 20.

In the early 1970s, Shanley was Boston’s “street priest.” Child Welfare workers found him an invaluable ally during an epidemic of teenage runaways, street hustlers, and drug abusers. His Boston Ministry to Alienated Youth earned credibility and respect. Shanley was, at the time, one of the few caregivers in Boston willing to deal non-judgmentally with gay teenagers. Of the hundreds he provided with care and counseling, none alleged any impropriety — not even when, at a time of anti-gay hysteria, Suffolk County DA Garrett Byrne set up a hotline to encourage anonymous reporting of homosexual crimes against minors.

In 1977-’78, while Anita Bryant’s “Save Our Children” campaign was in full cry, a scandal erupted involving Boston-area teenaged hustlers and their johns. When local press pumped public outrage into hyperdrive, the Boston/Boise Committee, an ad hoc group of queer activists seeking to address the situation, sponsored a public discussion on the crisis and its issues. Two organizations grew out of that meeting — the North American Man/Boy Love Association (NAMBLA) and Gay and Lesbian Advocates and Defenders (GLAD), a Boston-area legal resource still in operation.

Along with lawyers, social workers, and other clergy, Shanley spoke at the Boston/Boise forum. He did not publicly promote sex between men and boys, nor did he attend the post-meeting caucus at which NAMBLA was born. Although he is persistently depicted as one of NAMBLA’s founding members, Shanley has, in fact, no traceable connection to that small, diffuse organization.

Shanley did dissent from the Church’s positions on priestly celibacy. He openly supported Dignity, an unauthorized organization of gay Catholics. He now admits to having sex with both men and women over the course of many years, and with four of the countless older teenagers he met during the course of his street ministry. While many of his associates were aware that Shanley was attracted to young men, nobody suggested he was sexually interested in prepubescent boys until Ford and Busa came bobbing to the surface. At that point, the myth of his NAMBLA involvement helped make Shanley the star attraction of a multi-ring media circus that peaked with his arrest.

Freed on $300,000 bail, Shanley found housing in Provincetown, the resort community at the tip of Cape Cod, despite threats and hostility from predominantly gay local residents. For a long time his criminal case remained dormant. Meanwhile, basking in victimhood through numerous TV appearances, Greg Ford and his parents led the effort to obtain damages from the Archdiocese of Boston. In April 2004, without conceding any culpability in the Shanley case, Archdiocesan officials approved payments said to total more than $1.2 million to the four Shanley plaintiffs. (Seven months before, the Archdiocese had reached an $85 million settlement with 550 more purportedly devastated victims of priestly fondling and fellatio, real and imagined.)

During this period it became clear that Greg Ford, the instigator of the Shanley case, was a loose cannon who could not seem to keep his stories straight. Fearing Ford could jeopardize her efforts to convict Shanley, Middlesex County DA Martha Coakley dropped him as a plaintiff — along with fellow accuser Anthony Driscoll — in July 2004. Driscoll, another Ford classmate, also based his allegations on recovered memory.

“Ford’s case was meant to be a slam-dunk,” notes ex-seminarian Paul Shannon, one of Shanley’s few public supporters. “If the case that was supposed to guarantee a conviction has been dropped for lack of credibility, what does that say?”

As The Guide goes to press, prosecutors are preparing to drop one more accuser — an individual known chiefly as “Male No. 4,” who has a history of homelessness and substance abuse — because of his reluctance to cooperate at Shanley’s pretrial hearing. This 35-year-old, whose whereabouts are often unknown even to the prosecutors, refused to return to complete his testimony following a session where Frank Mondano, Shanley’s attorney, dismantled his repressed-memory scenario during cross-examination.

Some observers say the Middlesex County DA’s Office would retreat from Shanley altogether if it weren’t for the perceived necessity to save face. Another consideration may be that the professional abuse-victim community of Massachusetts is determined at all costs to make an example of Shanley. (The state’s other star-quality clerical sex-abusers are dead, dying, and semi-forgotten. Father John Geoghan, serving a ten-year sentence for touching a boy’s backside, was murdered in his cell in 2003; Father James Porter, convicted of molesting 28 children, remains behind bars with terminal cancer.)

A third factor may be DA Coakley’s wish to validate recovered memory evidence in Massachusetts. The use of such evidence has declined since the early ’90s, and has been forbidden or curtailed in some jurisdictions in response to scientific evidence refuting its existence. But Coakley, who in 1991 attained local celebrity during the sensational (and bogus) recovered-memory prosecution of Lowell, Mass., grandparents Ray and Shirley Souza, seems to have a particular affinity for the dissociative-amnesia mythos.

Paul Busa, the most presentable of the Shanley Four, remains in the case, but apparently with some reluctance. At one point Busa — who appeared to welcome notoriety two years ago — announced that he would refuse to testify if named in the press. Coakley obligingly obtained a judicial decree forbidding publication or broadcast of Busa’s name. Citing First Amendment concerns, however, the Associated Press, the Boston Globe, and the Boston Herald went to court and had the ban rescinded.

Sources close to the Middlesex County DA’s office say that Shanley recently refused a deal offering two years’ house arrest for an admission of guilt. While some criminal justice activists hope for an acquittal, Shanley’s supporters are not universally optimistic.

“In the present climate,” says Paul Shannon. “A jury would convict him on the testimony of a ham sandwich.”

Note: The most comprehensive account of the Shanley case now available is JoAnn Wypijewski’s “The Passion of Father Paul Shanley” in the September/October 2004 issue of Legal Affairs. The piece can be read online at www.legalaffairs.org/issues/September-October-2004/.